When I came out as a transgender woman publicly on 1 March 2021, I had no thought for the proximity of International Women’s Day. Having identified as female my entire life I’m still coming to terms with what it means to be a woman and learning about myself and my place in the world. Two years ago I think I would have believed it impertinent and misplaced to announce my gender to the world on a day designated to celebrate the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women. Today I still feel tentative about connecting my womanhood with International Women’s Day, but for different reasons, and I’m now more assertive about elbowing my way into society and claiming my rightful place.

As I’ve progressed through the last two years of being out full time in the world, I’ve given a fair bit of thought to what it means to be a woman. In part, my existence and appearance are due to the wonders of modern medicine and a society that has managed for the most part to untangle the concepts of sex and gender. The recognition that gender is a social construct that does not conform to a binary model and has little if anything to do with chromosomes and genitals is an important breakthrough. But, as much as medicine and a progressive society has enabled my existence, it also constrains it.

I first attempted medical transition in 2009. The two doctors I saw were Perth’s leading specialists in transgender medicine at the time and both male. Both were tentative about my identity and reluctant to validate it, because I didn’t conform with their idea of what a transgender woman looked, acted and sounded like. They drove me back into my hell of internalised transphobia, a place from which I didn’t emerge for another decade. With hindsight, I now understand that the problem was them not me. These doctors represented a profession that was still very much male dominated and at that time, transgender medicine was all about gatekeeping. The diagnosis of gender identity disorder was introduced into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980, where it was classified as a mental illness. It wasn’t until the publication of the fifth iteration of the DSM in 2013 that the concept of gender dysphoria was introduced. This change in terminology in part was a recognition that being transgender is not a mental illness and has led to more progressive approaches to treatment of gender dysphoria based on a person-centred approach and informed consent.

In 2009, I had to demonstrate that I was sufficiently in charge of my faculties to be able to make decisions about my medical treatment and understand the potential consequences and outcomes. I also had to meet cis males’ ideals and expectations of what it means to be a woman. I’m sure those cis males were clear that their ideas of what it means to be a woman were appropriately evidence based, but how could they possibly know? By the time I returned to the medical profession to seek support with transition, things had changed, and so had I. I was clearer and more resolved about who I am and what I needed from my doctors. This time around, starting in 2018, I selected my own team of doctors starting out with a general practitioner. I recall very well my first meeting with her. I deliberately chose not to select from the list of doctors on the Internet that other trans people had identified as ‘trans friendly’, a term I have very conflicted views about. I picked a female doctor in a surgery that has a reputation for excellence and when I turned up for my first appointment I told her I was there to interview her. When I’d finished explaining what I needed she told me she didn’t have any experience in the field of transgender medicine, but she was willing to learn if I was willing to have her as my GP.

Mr relationship with my GP was a key turning point in my medical transition. It was her who referred me to other carefully selected specialists as we needed them, and it is this woman who continues to support my physical, mental and emotional journey to this day. For me, my relationship with my GP is proof that anyone, any service provider, can be ‘trans friendly’ if you’re willing to go the journey with them. I have found that taking this approach has expanded my choices and I now spend my time in the world expecting that everyone will accept me for who I am, rather than constantly seeking the unicorn of the ‘trans friendly’ this and that, an approach that, in my view, leads to more fear and exclusion rather than the opposite.

However, in trans medicine, there are still the remnants of the idea that that the medicos know best, not only who you are, but also how you should be supported to become yourself. The stereotype of the ideal woman still echoes strongly through the institutions of medicine, and this is reflected in the treatment options that are presented. There are feminising hormones, designed to give a person the secondary sex characteristics of a woman; the various surgeries including facial feminisation surgery and what is now called ‘gender confirmation surgery’ which for trans women focuses mainly on the creation of a vagina and breasts.

Consider the term ‘gender confirmation surgery’. How can this concept be anything but the imposition on trans women of a cishet (largely male) view of the feminine ideal? Yes, it is a valid option for some, but its continued prevalence in the media and folklore of what it means to be a transgender woman is an inaccurate reflection of transition for many people.

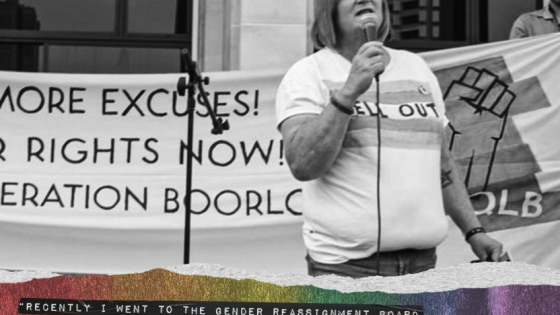

Increasingly gender non-conforming people identify as non-binary and this, along with the idea of gender fluidity is giving lie to the idea that gender identity has to be male/female and fixed. While to those with lived experience these realities are obvious, governments, the medical profession and broader society are taking a long time to catch up. For example, the Gender Reassignment Board in Western Australia and the Gender Recognition Panel in the UK only recognise gender as binary, non-binary identities are still not legally recognised. While this remains the case, there will continue to be a majority of gender diverse people who cannot be legally identified as themselves. Worse, if they want medical treatment, they still have to navigate a system that focuses on the binary and is still severely limited in how it defines female and male, let alone the infinite range of other gender identities.

The upshot of all this is that we still have a long way to go. In my case, I identify as female and am working towards contributing to a society in which I am viewed by all as myself without question or expectation that I should live up to any ideal but my own. I want to be seen as someone who can contribute to the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women because and regardless of my transness. I am as much a woman as anyone who identifies as female, and I will no longer accept being steered or guided down any path that is designed to meet medical, legal or social expectations that are counter to who I am. I am a woman and today is my day.